FLORIDA — A provision of a Florida medical marijuana law has caused much controversy among black farmers in the state who say it’s shutting them out of the potentially lucrative industry. This group has now taken their fight to the Florida legislature in the hopes of passing an amendment that takes the regulation out of the bill.

Last year, Florida Governor Rick Scott (R) signed the Compassionate Medical Cannabis Act, which allows some nurseries in the state to grow and distribute low-THC marijuana to patients who suffer from cancer, seizures, and muscle spasms. But the law stipulates that those who qualify for licensing must have operated as a registered nursery in Florida for 30 consecutive years — a criterion that many, if not all, black farmers in the state can’t meet. Farmers of color say they’ve been hampered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s past discriminatory practices that have made it difficult for them to thrive in the industry.

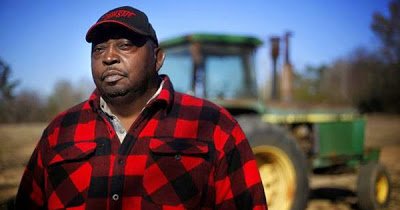

“There weren’t that many black farmers 30 years ago in the nursery business,” Howard Gunn, Jr, the president of the Florida Black Farmers and Agriculturists Association, told FOX News. “Because of that, we weren’t able to produce as much or be as profitable as [other] farmers. If we found one [black] farmer growing that many plants, it would be surprising.”

But altering the language in the 2014 legislation has proven to be an uphill battle. When Florida Sen. Oscar Brayon, a black Democrat who represents Miami, introduced an amendment earlier this year, a Republican colleague reportedly tried to convince him to withdraw it, promising that he would change the language in the bill with another piece of legislation that would end legal challenges in the bill Gov. Scott signed last year. An early end to the session, however, thwarted those plans.

Expanding entry into the medical marijuana industry could prove immensely beneficial to vendors of colors and their clientele. Medical marijuana advocates say that the plant can treat symptoms of HIV/AIDS, anxiety disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and other ailments that disproportionately affect black Americans. With Florida’s current law in place, however, the likelihood of a black-owned farm winning one of five licenses the state will award remains slim.

The provision of the Compassionate Medical Cannabis Act notwithstanding, black people — a group that accounts for a significant portion of marijuana arrests and convictions — find difficulty entering the medical marijuana industry, which experts say can garner $5.6 billion in annual sales. In many states that have legalized medical marijuana, people with drug-related felony convictions cannot open their own businesses. Additionally, nonrefundable application fees and annual licensing fees for medical marijuana dispensaries often total tens of thousands of dollars, further keeping opportunity at arm’s length for anyone who wants to take on the entrepreneurial endeavor. Opening a clinic at home isn’t an option either. Besides Arizona, legally growing and selling medicinal marijuana in one’s residence isn’t a viable alternative in any of the states that have medical marijuana laws in place.

In a column published at Madame Noir last year, writer Charing Ball noted that consumers of color with medical issues also face challenges in smoking legally, despite the passage of laws that protect their right to do so. High prices can compel some to resort to the black market for their product. Doing so creates a demand among black market distributors, many of whom wouldn’t be able to enter the medical marijuana industry legally. With decades-long drug laws still on the books, people of color still get shorthanded at a time when the War on Drugs has come under more scrutiny.

With Florida’s legislative session well behind, advocates’ focus has shifted to the next meeting of lawmakers with the hope that the amendment gets reintroduced and approved so that black farmers can enter the medical marijuana market without difficulty.

Regardless of the outcome, the current case in Florida has reminded some farmers of color that their economic position didn’t occur by happenstance. During the Reconstruction Era, the USDA marginalized black farmers because of fear among white farmers about competition from freed slaves. Institutionalized practices — like the policy under scrutiny in Florida — have kept black farmers out of the industry since then. For example, freed slaves couldn’t receive farming loans without credit history.

The USDA later marginalized farmers of color by increasing tax sale, seizing of land through eminent domain, delaying loans until after the end of the planting season, and denying crop disaster relief funds. By the early 1990s, the black farmer population fell by nearly 100 percent, eventually prompting a class action lawsuit against the USDA that resulted in the allocation of more than $2.3 billion to more than 13,000 farmers. In their appeal to Florida state lawmakers, the Black Farmers and Agriculturists Association cited that court case, called Pigford v. Glickman.