ANNAPOLIS — William S. Keyes is 93-years-old. He was a Washington, D.C. police officer, worked in the U.S. Postal Service, ran his own business and bravely served in World War II. And, by the way, he is still a substitute art teacher at South River High School where his daughter, Jutta says his students simply adore him. As proof, Keyes rumbles through the amazing museum he has on the grounds of his Annapolis home and produces a book that his pupils put together for him.

“I still get to go and teach the children who really appreciate me,” said Keyes, who served in the Army from 1939 to 1945. His highest rank: sergeant. And, the ever-humorous Keyes explains, “I got demoted so many times in the Army that I had a zipper on my stripes. No kidding, I still have the letter they gave me that said they don’t need anymore black officers.”

With a wry sense of humor and in a way that only veterans of his era can explain Keyes said the military was kind to him only in that it got him fired from the D.C. police force, helped him to meet his four wives and allowed him to understand the only two things that can be credited with his longevity.

“This nice glass of Sherry that I’m drinking and a little Viagra,” he said.

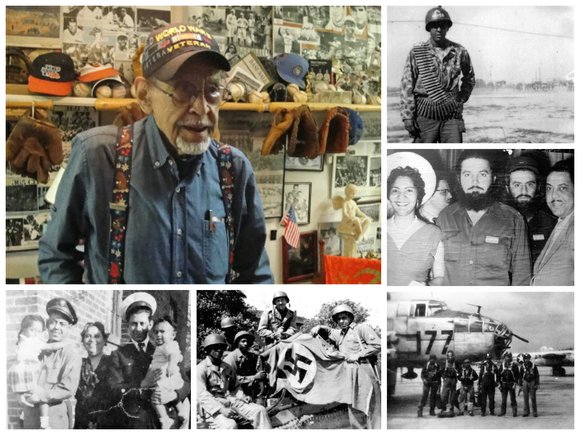

Keyes said he doesn’t think too much about World War II, his thoughts often settle upon what he calls more important history, including the Buffalo Soldiers. He owns a replica uniform and a slew of authentic artifacts that decorate his museum, a structure on his property that contains photos like that of Cuban strongman Fidel Castro from 1958; a victorious picture of his Army troop holding a captured Nazi flag during the war; and one he took in England where he stands tall with a .50 caliber machine gun.

Keyes said he has a special affinity for the Buffalo Soldiers and he even has a signed document certifying the success of African-Americans in the Civil War before freedom had even been put on the table and the Emancipation Proclamation conceived.

“You know late in the 19th century the Buffalo Soldiers represented an important part of the Army’s strength and they had some real significant contributions,” Keyes said. “Of course, their accomplishments were always downplayed or ignored because they were black, but they were so important,” he said.

His museum contains tons of other war artifacts and autographed memorabilia from the Negro Leagues, all of which probably should be displayed in one of the more prominent museums in the country.

“It’s a life’s work that I have in here,” he said. “My war medals, awards, certificates. I’d like to have it housed in a museum, not in some old box where people just pick through it.”

Keyes’ personal museum also contains original paintings and drawings. Included in the priceless artifacts, collections and memorabilia are photos of his father’s restaurant outside the old Griffith Stadium in Washington. There are baseball bats and gloves signed by Negro League stars and baseball Hall of Famers including Cool Papa Bell and Josh Gibson.

“You know, my wife wanted me to get rid of this place. She said I should toss all of this stuff, but you know I never listened to that,” he said.

Keyes says he is always confronted with questions about World War II. It’s no wonder. He usually sports a cap with the words, “World War II Veteran,” inscribed on the bill and he enjoys donning a bright blue jacket that has his favorite American Legion Post inscribed on the front.

“I give the people what they want,” he said, with what some have referred to as a devilish smile.”

“He is so aware of history, the global situation, racial politics and he’s always interested in what’s new in the world,” said his daughter, Jutta. “He had such a global perspective of the world ever since early on in his life. His interests are so varied and it’s a good thing to

know, from his standpoint, that as he’s gotten older, so many people value his opinion. Usually, when people get older they tend to get pushed aside. Not him.”

One conversation with Keyes and it’s easy to see why it’s impossible to cast him aside.

“I’ve got a big mouth,” he said. “It’s just like when someone walks in here and looks at my museum and I tell them that this is also a secret place where I bring all my women. They laugh, but they don’t know me too well.”