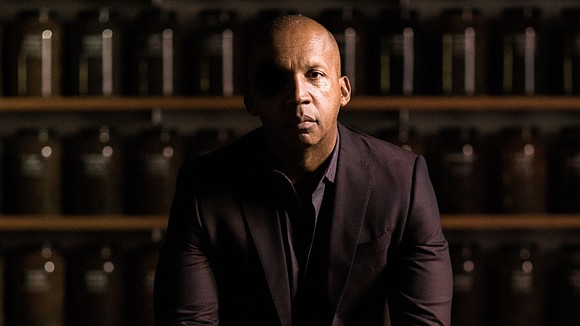

“Let’s keep fighting!” Bryan Stevenson implored the audience as he stood on stage with Jamie Foxx, Michael B. Jordan, Brie Larson and other cast members of the film Just Mercy, based on his bestselling book of the same name, at the latest NAACP Image Awards. What the Harvard trained defense lawyer and longtime criminal justice activist was referring to was fighting inequities in the US criminal system that harshly discriminates against Black and Brown people, and the poor of all races.

Perhaps the Delaware born and raised Stevenson got this spirit of justice and courage from his mother. She was a woman who urged little Bryan and his sister to get back in a hotel swimming pool hastily exited by a group of outraged whites when he and sister entered as pre-teens. It was also his mother who forced Bryan to apologize, hug, and say “I love you” to a little boy in his community after he had joined his peers in making fun of the little boy’s speech impediment. These were lessons in courage and compassion that Stevenson never forgot and those two characteristics define the work he’s been doing for over thirty years.

Working as a defense lawyer and criminal justice crusader for over twenty years now, Harvard-educated Stevenson has freed multiple innocent men such as Walter McMillan from death row after many years. He’s also become a leader in the movement against mass incarceration. The organization provides legal representation to prisoners who may have been wrongly convicted and to those who may not have received a fair trial.

Stevenson, beginning to realize that much of the sentencing was unfair and discriminatory, started his non-profit, the Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama in 1989.

We arrived at massive inequities in the criminal justice system, Stevenson believes, by people’s feigned and real ignorance. “We have to educate people and once we do that, people can’t say they didn’t know.” To that end, Stevenson who is also an talented pianist, has branched out from solely being an actor in the criminal justice system to using culture to frame the narrative around America’s criminal justice system, which includes the history from which it’s derived.

After twenty years of fighting behind the scenes for justice, Stevenson realized that he needed to make his voice heard more loudly and to shape a narrative that is closer to what he has personally observed, and to provide solutions. “I realized, we should start talking more publicly to create the environment that we need to execute justice.” The book was the first part of that, and it’s the reason he consented to the film adaptation.

When the opportunity to film Just Mercy came around, he thought it would be a great vehicle for raising people’s consciousness. “A lot of people will see a movie who won’t read a book and if you can use two hours to get people to understand really complex issues and think about them, that’s, that’s an opportunity you don’t want to miss.”

In addition to the book and the film, Stevenson has opened a museum and memorial in Alabama to visually memorialize the thousands who have been lynched. The National Peace and Justice Memorial and just steps away, the Legacy Museum, provides a symbolic thruway showing the connection from slavery to the disparities in law enforcement we see today.

Perhaps the most prominent exhibit is the one consisting of 800-plus hanging steel rectangles inside the museum. These name and represent each of the counties (and their states) where a documented lynching took place in the United States. Outside are corresponding temporary markers which each state is encouraged to retrieve and use for their own commemorations of lynching. Maryland has retrieved theirs. “There’s been a pretty active movement in Maryland and the state legislatures actually commissioned people so there’s this group of people working across the state to erect markers on lynching sites. We’ve worked with people in Wicomico County, Anne Arundel County, Prince George’s County. There is a pretty active community of people who are working on this.”

Says Stevenson, “It’s shameful that it’s the 21st century before we actually have cultural institutions that even talk about slavery or lynching. We’re at the very beginning of what I hope will become a cultural revolution that makes it impossible for people in this country, to live here without full awareness and knowledge about the damage that was done.”

Please visit https://eji.org/ for more information.