A car accident at 20 years old left a French man in a vegetative state for 15 years. But after neurosurgeons implanted a vagus nerve stimulator in his chest, the man, now 35, is showing signs of consciousness, according to a study published Monday in the journal Current Biology.

Vagus nerve stimulation is already used to help people with epilepsy and depression. This cranial nerve runs from the brain to other parts of the body, including the heart, lungs and gut; vagus means “wandering” in Latin.

The study results challenge ideas that consciousness disorders lasting longer than 12 months are irreversible, the researchers believe.

A demonstration of what’s possible

Vagus nerve activity is “important for arousal, alertness and the fight-or-flight response,” wrote Dr. Angela Sirigu in an email. She is an author of the study and neuroscientist at the Institut des Sciences Cognitives Marc Jeannerod in Lyon, France.

Sirigu and her colleagues decided to test the ability of vagus nerve stimulation to restore consciousness in a patient in a vegetative state. Patients in a vegetative state show no evidence of consciousness, mental function or motor function. Unlike a coma, a vegetative state includes intermittent periods of eye opening; this seemingly hopeful sign, though, is not a normal waking, just a random physiological occurrence.

Vagus nerve stimulation begins with a surgeon implanting a device in the chest and threading a wire under the skin. This wire joins the vagus nerve and the device, which sends electrical signals along the nerve to the brain stem (where the spinal cord and brain connect) and in turn this transmits impulses to certain areas in the brain.

Stimulating the vagus nerve activates “a natural physiological mechanism,” wrote Sirigu in an email.

Sirigu and her colleagues selected the man, who had been in a vegetative state for 15 years “showing no sign of change since his car accident,” she wrote. “We therefore put ourselves in a difficult challenge by selecting a patient with the worst outcome.”

The reason for that choice is that if any changes occurred in the patient after vagus nerve stimulation, then “these could not be the result of chance,” she added.

After a single month of stimulation, the patient’s attention, movements and brain activity significantly improved, according to the authors.

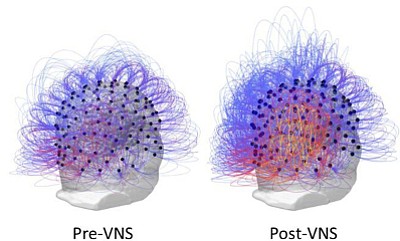

“Our results show major changes at the brain level,” Sirigu said. One electroencephalogram or EEG signal, “a brain rhythm previously shown to distinguish vegetative from minimally conscious state patients, significantly increased,” she wrote, particularly in areas important for “movement, body sensations and awareness.” A PET scan, a type of imaging test, showed increases in metabolic activity in the brain, as well.

Dr. Nicholas Schiff, a neuroscientist at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian who also researches consciousness, said some will look at this case and say, “It’s one patient, and they didn’t really move him into a new functional category. And then they will say, ‘What’s the point here?’ ” said Schiff, who was not involved in this study.

Yet the new study is “another demonstration of what is possible to do, and it’s a new technique, and it might have some real advantages for some patients,” he said.

The human brain’s ‘greater potential’

“The general point here is that taken together with all the other information that we have now, it’s very clear that the severely injured human brain has greater potential than it’s given credit for,” Schiff said. “So you can lay around for years and, in principle, still be responsive to medications, devices and other things.”

Even with that much brain injury, you can still “move the dial,” said Schiff.

What’s new in this study is stimulation of the vagal nerve on the outside of the brain, he said. “The nerve sends impulses down into the stomach area,” he explained. Instead, the researchers send impulses up through the nerve, and that activates the brain through multiple synaptic pathways.

In the United States, an estimated 50,000 patients are in a vegetative state, and about 300,000 are in a minimally conscious state, Schiff said.

“We’ve now known for a long time that we can do something for very severely injured brains, but the science has not been met with any kind of infrastructure to catch up with it,” he said. More funding for research is needed, he added.

Dr. James L. Bernat, a professor of neurology and medicine at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, referred to the new case report as “provocative” and “exciting.”

Bernat, who also was not involved in the research, praised Sirigu and her colleagues for their choice of patient: someone in a long-term vegetative state.

“If they had, for example, chosen someone who had been in a vegetative state for three months after a traumatic brain injury and then showed improvement a month later with the intervention, a critic might say, ‘Well, wait a minute. We know that a lot of people who are vegetative for three months spontaneously improve in that time period, so it may not be the intervention,’ ” Bernat said.

He noted that every case of vegetative state is unique based on what caused damage to the brain, how severe that injury was and what regions were harmed.

A vegetative state can be caused by a variety of injuries, including traumatic brain injury, injury to neurons caused by a lack of oxygen and blood flow during cardiac arrest or meningitis, he explained.

For these reasons, the vagus nerve stimulation technique will not work with all patients, Bernat noted, still it’s worth doing more studies to find out which patients will benefit from it.

A better understanding of how brain damage harms consciousness would involve learning about how the brain maps the pathways of normal consciousness, said Bernat. “How does normal consciousness occur? And how does unconscious occur?” Bernat asked. “There’s a lot of basic work that needs to be done.”

Plausibly, this work would also contribute to explaining neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s disease, as well as cognitive impairment resulting from traumatic brain injury.

New research of consciousness “has the potential to extend beyond the relatively small group of people who have these conditions,” said Bernat. Consciousness disorders are, in a sense, “an orphan group of diseases that has been somewhat neglected, not entirely, but somewhat by funding agencies,” Bernat said. “I would like to see more funding for research.”

Sirigu said she is planning a large study involving collaboration with several research centers to confirm and extend the therapeutic potential of the vagus nerve stimulation technique.

“More basic research will also be important for advancing our understanding of this fascinating capacity of our mind to produce conscious experience,” she said.