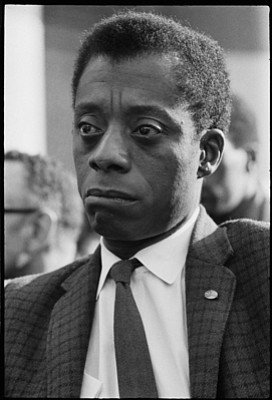

In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, “Remember This House.” The book was to be a revolutionary, personal account of the lives and successive assassinations of three of his close friends— Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

At the time of Baldwin’s death in 1987, he left behind only 30 completed pages of the manuscript. Now, in an incendiary new documentary, master filmmaker Raoul Peck envisions the book James Baldwin never finished.

The result is a radical, up-to-the-minute examination of race in America, using Baldwin’s original words and a flood of rich archival material.

The film, “I Am Not Your Negro,” is a journey into Black history that connects the Civil Rights movement to the present Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

The film questions Black representation in Hollywood and beyond. Ultimately, it confronts the deeper connections between the lives and assassinations of the three African-American leaders in a work that challenges the definition of what America stands for.

“I started reading James Baldwin when I was a 15-year-old boy searching for rational explanations to the contradictions I was confronting in my already nomadic life, which took me from Haiti to Congo to France to Germany and to the United States,” Peck said.

The director noted that he grew up “in a myth in which I was both enforcer and actor— the myth of a single and unique America. The script was well-written, the soundtrack allowed no ambiguity, the actors of this utopia, Black or white, were convincing,” he said.

With rare episodic setbacks, the myth was strong, better; the myth was life, was reality, he said. “I remember the Kennedys, Bobby and John, Elvis, Ed Sullivan, Jackie Gleason, Dr. Richard Kimble, and Mary Tyler Moore very well,” Peck continued.

“On the other hand, Otis Redding, Paul Robeson and Willie Mays are only vague reminiscences. Faint stories tolerated in my memorial hard disk. Of course, there was “Soul Train” on television, but it was much later, and on Saturday morning where it wouldn’t offend any advertisers,” he said.

In the course of five years, Evers, Malcolm X and King were assassinated. Peck says each of them was connected and not just by the color of their skin.

“They fought on different battlefields,” Peck said. “And, quite differently. But in the end, all three were deemed dangerous. They were unveiling the haze of racial confusion. James Baldwin also saw through the system. And he loved these men. These assassinations broke him down.”

A Los Angeles Times review of the film notes that it’s Baldwin himself we see at the start of the film, a guest on a 1968 episode of the Dick Cavett Show being asked by the host “Why aren’t Negroes more optimistic – it’s getting so much better.”

“It’s not a question of what happens to the Negro,” Baldwin said with a look of inexpressible weariness crossing his face. “The real question is what is going to happen to this country.”

This is the theme— the idea that what’s really at stake in racial matters is America’s soul that Baldwin returns to again and again in the course of the film.

“The truth is this country does not know what to do with its black population,” he said at one point, adding later “Americans can’t face the fact that I am flesh of their flesh.”

Perhaps most movingly, in a televised interview with psychologist Dr. Kenneth Clark, Baldwin says he is “terrified at the moral apathy— the death of the heart which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves so long that they really don’t think I’m human. And this means that they have become, in themselves, moral monsters.”

But before it gets to any of that other material, “Negro” cuts immediately from that black-and-white Cavett footage to a sizzling montage of photos from Ferguson and other contemporary scenes of struggle, brilliantly edited to Buddy Guy’s high-octane “Damn Right I’ve Got the Blues.”

The film is opens for a one-week Academy-qualifying run and returns on Feb. 3 to theaters around the country, including Baltimore.

Note: “I Am Not Your Negro” has been nominated for “Best Documentary Feature” by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (Oscars).