ITHACA, N.Y. (CNN) — Don’t be fooled by the bucolic scenery or the leafy college campuses; Ithaca, New York has been rocked by the scourge of the heroin epidemic sweeping the United States.

Suffering from the drug epidemic isn’t what sets Ithaca apart. It’s how their mayor wants to deal with it that makes Ithaca unique.

CNN Video

Ithaca’s plan to fight heroin by allowing it

Like much of the nation, Ithaca, NY is facing a heroin crisis. To fight this, the mayor has proposed opening a supervised site for users to inject heroin legally.

The city is nestled along the southern shores of Lake Cayuga and consistently recognized as a great place to live in United States. Home to three colleges, it’s one of the nation’s “Smartest Cities” and boasts low rates of unemployment. But since 2005, eleven people here have died here from opioid overdoses. Seven of those occurred in the past two years. And in a one-month stretch this spring, four Ithaca residents lost their lives.

In response, Ithaca Mayor Svante Myrick has proposed launching a program that has never been legally attempted in the United States: Giving addicts a clean and safe place in the city to use heroin in town.

“The first time I heard it, it sounded like we were just enabling people to do drugs,” Myrick said in an interview with CNN in his downtown office. “But the truth is, in the places where it has worked, more people get off of drugs.”

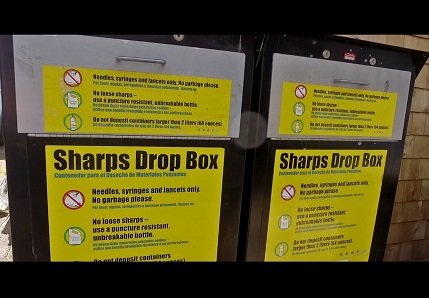

The first legal “supervised injection site” opened in Bern, Switzerland, in 1986, and others have since sprung up throughout Europe and in Australia and Canada. The facilities provide access to clean needles and other supplies involved in heroin use untainted by diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C. Users consume the drugs in the presence of a professional trained in treating overdoses, and others who can provide referrals and access to treatment programs. Supporters say this is a superior way to keep dirty needles out of the community and bring addicts out of the shadows.

The idea was just one of many that Ithaca’s city government proposed as part of a municipal plan to combat drug abuse, the culmination of a two-year study that included participation from city leaders, social workers, drug policy reform experts, law enforcement, recovering addicts and focus groups involving members of the community.

Ithaca’s movement on this issue comes at a time when policymakers are changing attitudes toward tackling drugs. Opioid overdose is the leading cause of unintentional death in the United States. The dire problem has prompted President Obama to expand federal treatment programs. In March the Senate passed a sweeping bill to address addiction problems and the House passed a slew of bills related to the issue in May. And it has played a significant role in both party’s presidential nomination contests, with almost all candidates weighing in.

But Ithaca’s leaders say they’re tired of waiting for a federal response.

“The state and federal government have failed. They failed,” Myrick said. “We needed a solution because we are tired, I am tired of waiting. I’m living a nightmare. Too many brothers and sisters are dying. I just didn’t want to wait.”

The plan revolves around three focused pillars: Prevention, treatment and harm reduction, and stands as a stark alternative to the way the United States has traditionally responded to drug abuse.

On the question of building a supervised injection site, however, Myrick will have to wait. Heroin is still illegal, and while other American cities have considered launching similar programs without a state or federal blessing, Ithaca won’t proceed without state authorization. New York State Assemblywoman Linda Rosenthal, a Democrat from Manhattan, plans to introduce a bill to make such sites legal statewide, which would pave the way for Ithaca.

Although a broad group of Ithaca officials were involved in the overall plan, some—including the chief of the city’s police department—haven’t endorsed every proposal, including the idea of a supervised injection site.

“I am a law enforcement officer. I took an oath to uphold the law and right now under the law heroin is considered an illegal substance,” said Ithaca Police Chief John Barber. “So I’m not going to condone the use of heroin whether it’s in a facility or not. If it’s allowable under the law then so be it, we will conform with the law, but currently it just isn’t.”

Barber still considers himself an ally of Merrick and supports the spirit of a drug initiative that treats the problem like a health issue instead of a criminal one. Every officer, for example, is trained in the administration of Narcan, an opiate antidote that combats overdoses.

“At this point law enforcement isn’t really equipped to do much more than in effect arrest and put people into the criminal justice system,” Barber said. “This really is a medical crisis. It’s a crisis that I don’t believe we can arrest our way out of.”