One year ago, when Freddie Gray was laid to rest, the city of Baltimore erupted in riots. Protests gripped the city as stores burned, cars were set afire, a Baltimore Orioles game was closed to fans and anger stirred.

(Courtesy Photo)

Brandi Worley teaches fourth and fifth grade at Mount Washington Elementary School.

Today, a year later, students in at least two local schools are trying to make sense of why police and the African-American community have such a hostile relationship. Through discussions driven by fourth, fifth and sixth graders at Mount Washington Elementary School and Calverton Elementary Middle School, young ones have been expressing their thoughts about the chaos.

“We’ve looked at race relations, the students’ perception and where the race problems stem from,” said Brandi Worley, who teaches fourth and fifth grade at Mount Washington.

“Police brutality has been a big topic and the students see a difference among blacks and whites and among those of different religions,” said Worley, who began teaching through Urban Teachers, an organization committed to transforming urban schools by preparing highly skilled, deeply committed teachers who know how to improve outcomes for all learners.

The organization strives to improve outcomes for thousands of urban students each year.

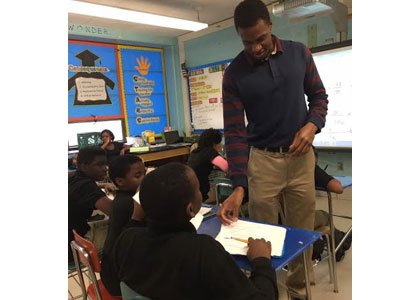

Corey Gillis, who teaches sixth grade math at Calverton Elementary says his approach in tackling the riots in his classroom, involves civic lessons that use mathematics.

“I want the students to think about how the riots have impacted the community financially and I want them to focus the conversation from the lens of what is important to them,” said Gillis, also a product of Urban Teachers.

Gillis says the Baltimore riots and Gray’s April 19, 2015 death will remain a topic and an important teaching tool.

“I try to be the facilitator and I make sure that they maintain a positive tone because bashing and being violent toward people won’t get us anywhere,” he said.

With the help of teachers like Worley and Gillis, young students are coping despite reminders of the unrest that gripped their neighborhoods a year ago.

The teachers have encouraged the students’ participation in creating strategies that will allow young ones to cope as well as understand the realities of a world still wrought with racism and mistrust.

“The students, at their young age, are disgusted with the way adults behave when it comes to race,” Worley said. “But, they determine through conversation where the problems with race stem from. For instance, we talk about how black slaves were treated as property by their slave owners and, even though the slaves outnumbered the masters, they were still [helpless].”

Students in Worley’s class are provided an outlet in which they dissect why individuals are treated differently because of race.

“They talk about Freddie Gray, Black Lives Matter and the students are genuinely curious because they don’t see race as adults do,” Worley said.

Gillis, who grew up in the Bronx, New York, said he refrains from presenting his own ideas and information, instead he allows his class of sixth graders to develop discussions about the riots and the impact it has had on Baltimore and its residents.

“I just don’t give them information, I give a problem and I want them to think about it, talk about the problem and come up with solutions because things are not just given to you in real life,” Gillis said.

The goal is to help the students learn to be independent thinkers, which Gillis believes could help prevent riots and unrest. He said many of the students live in neighborhoods where police are often around because of drug and other criminal activity.

“I want them to realize that police officers are people too. My students may have siblings or other relatives who dislike the police, but they’re people and our discussions help to defuse falsities,” Gillis said.

Discussions between the pupil and the educator, underscores another important factor in the success of the Urban Teachers program: in most cases, the teachers who emerge from the program usually can relate well to their students.

“I know what it’s like to grow up poor and in a single-parent household,” Gillis said. “My sister was my parent, my birth mother was a crack addict and my birth father distributed crack. I understand where we come from and I was able to overcome a lot of things and I know my students can overcome them, too.”