(CNN) — Debra Aust sees it in videos of recent police shootings.

Alex Sproul reads about it in his Facebook feed.

Sheryl Sims senses it when she walks down the street.

They are three Americans from three different demographic groups living in three different states. And they believe the same thing: Racism is a big problem.

Their voices are just a few in a country of more than 322 million people. But they are far from alone.

In a new nationwide poll conducted by CNN and the Kaiser Family Foundation, roughly half of Americans — 49% — say racism is “a big problem” in society today.

The figure marks a significant shift from four years ago, when over a quarter described racism that way. The percentage is also higher now than it was two decades ago. In 1995, on the heels of the O.J. Simpson trial and just a few years after the Rodney King case surged into the spotlight, 41% of Americans described racism as “a big problem.”

Is racism on the rise in the United States? Has our awareness changed? Or is it a problem that’s been blown out of proportion?

There’s not a one-size-fits-all explanation for the shift. The survey of 1,951 Americans across the country, which CNN will release and discuss in detail Tuesday at 10 p.m. ET, paints a complicated portrait, highlighting some similarities across racial lines and also exposing gaps that seem to be growing.

But this much is clear: Across the board, in every demographic group surveyed, there are increasing percentages of people who say racism is a big problem — and majorities say that racial tensions are on the rise.

‘A different story’

It caught Debra Aust by surprise.

The 48-year-old white woman from Sterling Heights, Michigan, says she didn’t expect racism to get worse.

“It always seemed like it was getting better, like our generation was going to be better than previous generations,” says Aust, who participated in the CNN/KFF poll. “But the TV started telling us a different story, with all of these shootings by cops.”

For Aust, whose father and uncle both work in law enforcement, the news stories she’s seen about unarmed African-American men being shot by police have hit home. The officers should be held accountable, she says.

“What’s not helping is the police are getting off with a slap on the wrist. … If it was me, and I was black, and this was happening in my community, I would be furious,” she says.

The case of Walter Scott, who was shot in April by an officer in North Charleston, South Carolina, sticks out in her mind. The trial hasn’t started yet. The officer’s attorney says he plans to plead not guilty, and that race has nothing to do with the case. But Aust has already made up her mind.

“I mean, give me a break, he wouldn’t have done that if the man was white, and that’s the problem,” she says.

It’s gotten worse, not better, since the 2008 election of President Barack Obama, says Ellis Onic. The 56-year-old engineer in Balch Springs, Texas, who’s African-American, points to the 2012 shooting death of Trayvon Martin and this year’s Charleston church massacre as examples. Time and time again, Onic says, the justice system has failed.

“The white man has had his way for so long, they don’t think of it as racism. They think that’s just the way it is. … We have a long way to go, because the justice system is not right. Justice is corrupt,” he says. “That’s why she has the blindfold over her eyes and the scale slightly tilted, so you know that it can go either way.”

Jim Bruemmer sees things differently.

The white, 83-year-old retired advertising executive in St. Louis, who participated in the CNN/KFF poll, says media coverage alleging racism — particularly when it comes to law enforcement officers — has been overblown.

“I am troubled by the bias I see in the media, that seems to spend all its time talking about the bad policemen and the bad white people and ignoring the crime and the disastrous conditions that are occurring in large segments of the black youth,” he says.

Bruemmer says he’s had to look no further than a suburb of St. Louis to see that firsthand.

“The belief is so universally held among the people I know, that the whole Ferguson thing was a farce,” he says, “that ‘hands up, don’t shoot’ was baloney, that the police officer behaved in a very proper manner and saved his own life, possibly.”

Growing racism?

Gauging changes in racial attitudes is complicated, says Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, a professor of sociology at Duke University. Bonilla-Silva has a phrase he uses to describe the situation he sees today: “new racism.”

“After the 1960s and early 1970s, somehow we developed the mythology that systemic racism disappeared,” he says.

Racism remained, according to Bonilla-Silva, but became more covert.

“The main problem nowadays is not the folks with the hoods, but the folks dressed in suits,” he says.

“New racism,” he says, has been decades in the making. But something has changed in recent years — access to cell phones and social media.

Accusations that police use excessive force, particularly against African-Americans, for example, now can get far more attention — far more quickly — than ever.

Communities of color across the country can more easily connect, according to Bonilla-Silva, and people are picking up on patterns that scholars have long discussed.

“People are doing Sociology 101. They can connect Walter Scott, the assassinations of black folks in a church, the slamming of a girl in a school,” he says. “And then it’s across the nation. People are then connecting the dots and saying, ‘No more.'”

Growing awareness?

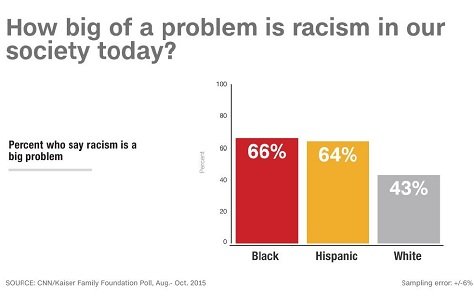

While the trend of a growing percentage of people viewing racism as a big problem in recent years was true across racial lines in the CNN/KFF poll, the share who see it as a problem is notably higher among blacks and Hispanics.

About two-thirds of blacks (66%) and Hispanics (64%) said racism is a big problem, while just over four in 10 (43%) whites said the same. Hispanics are much more likely now to say racism is a big problem than they were in 1995, when less than half responded that way. Among blacks, the share who said racism was a big problem dropped from 68% in 1995 to 50% in 2011, and now has climbed back to 66%.

Majorities across races said tensions between racial and ethnic groups in the United States have increased in the past 10 years. Roughly a quarter said tensions have stayed the same.

Sometimes the way people view racism can play out like a referee’s call in a baseball game, says Glenn Adams, a professor of psychology at the University of Kansas who has studied perceptions of racism.

“Is the guy out or safe? Well, it depends who you’re rooting for,” he says. “Sometimes it’s clear in either direction, but we tend to see it how we want to see it.”

It’s likely the level of racism in the United States is more or less the same, Adams says.

“What’s changed,” he says, “is that more people are aware of it.”

Knowledge of history, having friends who’ve experienced racism and personal background are all factors that can contribute to a greater awareness of racism, he says. And now, he says, there’s likely another factor at play.

“People are more aware of it because of the videos of police violence and the media attention. Now, the media report on it,” Adams says. “Black folks tended to know about this before. Now white folks are starting to know about it more. … Now, with this kind of evidence, people have to re-evaluate their sense of what is true and what is not true, so it becomes a little bit harder for people to deny.”

The same goes for repeated incidents of racism on college campuses, Bonilla-Silva says, like the chant that shuttered a fraternity at the University of Oklahoma and the noose found hanging at Duke this year.

It’s impossible to dismiss cases as isolated events, he says, when similar situations at schools and other institutions keep happening again and again.

“The fact that it keeps happening tells you that the problem is not a problem of bad apples,” he says, “but perhaps the problem is the apple tree.”

‘We’re all kind of in the same boat’

Because of his complexion, sometimes people think Rick Gonzales is Italian. Sometimes they think he’s Mexican or Middle Eastern. The experience, he says, has made him question the meaning of race.

“It’s obviously a label. Something tells me that we’re all kind of in the same boat, yet we’re separated somehow. We’re given different names,” says Gonzales, a 49-year-old truck driver from San Antonio, who participated in the CNN/KFF poll.

Gonzales’ mother is from Mexico and his father is from the United States. He says he feels that for people in power — most of whom are white — it’s advantageous to pit groups against each other. And to him, it seems like no matter what, darker-skinned people are at a disadvantage. That, he says, is why race — and racism — remain big problems.

“The ones that are usually getting the short end of the stick are the so-called minority … but we’re the majority, because we’re always the ones who are struggling,” he says.

Sheryl Sims, an African-American, 59-year-old retired teacher in Atlanta who participated in the CNN/KFF poll, says that for her, racism is something she senses when she walks down the street in her neighborhood.

“It’s just the way people will shun you,” she says, “or turn their head when you walk by.”

Things were worse 50 or 60 years ago, Alex Sproul says. But now, the 24-year-old, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and participated in the CNN/KFF poll, says he sees racism lurking under the surface.

From wage inequality to accessibility to jobs, Sproul says he feels minorities are still at a disadvantage.

Sproul describes himself as mixed race — Mexican-American and white. He says several events in recent years have made him feel racial tensions are on the rise.

One of them, he says, was the 2009 shooting death of Oscar Grant, an unarmed African-American man who was fatally shot by a police officer on a Bay Area Rapid Transit platform. Sproul says he first learned about the case when he was scanning his Facebook feed and saw posts from friends.

“You kind of see more of these situations, or extremes,” he says. “I don’t know if maybe it was going on before and there was no coverage, or if it’s happening with greater frequency.”

Too much hype?

Bruemmer, the retired advertising executive in St. Louis, says he sees racism as a big problem — but not for the reason you might think.

Too often, he says, leaders play the race card rather than addressing what he sees as the real issue behind many of the problems popping up in society today: broken families, particularly in the black community.

“The massive problem that I see is that our leaders at the highest level … do not even want to recognize or even acknowledge that this problem exists, and therefore they spend huge amounts of time demonizing the police force, throwing gasoline and making the problems much worse,” he says.

Racism is inevitable in any society, he says. But now, he fears that because of bad leadership, tensions are on the rise among some groups in the United States.

“I think the racism and the hatred of the white race has grown to the point where it’s worse than in the other direction. … I think the anger and the racism is much worse from black to white than white to black,” he says.

Searching for common ground

It’s hard to draw a clear conclusion when the reasons behind respondents’ answers to a survey question can vary so widely, says Mark Naison, a professor of history and African-American studies at Fordham University.

“People may agree that racism is worse,” he says, “and disagree profoundly on who the targets and victims are.”

“Simmering rage,” he says, has been fueled by backlash after Obama’s election, the economic struggles of lower- and middle-income whites and demographic shifts across the country.

“Latent racism is becoming more open, because a lot of people are feeling threatened,” he says.

But Naison says he’s also noticed a significant change in his classes.

“People are able to empathize, communicate and talk honestly across racial lines much better than they did five years ago, and certainly 10 years ago and 20 years ago,” he says.

Why? Naison says the changing world students are living in, full of far more multiracial families and friendships, has played a big role. A video of a police beating, he says, resonates for people now because they’re not looking at those involved as strangers.

“It’s not just that guy over there,” he says. “You could be beating my cousin or my boyfriend.”

The mix of “simmering rage” and growing empathy is a complicated equation, he says, that adds up to more people talking about race — and racism.

And it’s a conversation, according to Naison, that isn’t going away any time soon. If people from different backgrounds can open up about their concerns and find common ground, it could be a good thing, Naison says, like a therapy session on a national scale.

“That conversation is difficult,” he says. “But our history is difficult. Our present is difficult. We need to talk about it.”