(CNN) — The American economy has added an average of 261,000 jobs every month for the past 12 months, with March’s jobs report showing a slowdown to 126,000 jobs. Average hourly wages bumped up 7 cents in March, but have only grown by 2.1% in the last 12 months, a meager 52 cents per hour.

If job growth has been strong, why aren’t wages going up?

Weak wage growth puzzles economists. After all, as the labor market improves, workers should be able to get raises as employers compete for a tighter labor force. But that isn’t happening, for four reasons.

First, a lot of people still are out of work due to the persistent damage from the Great Recession and the weak economic recovery. Economists measure not only unemployment, but also “labor force participation” which includes not only workers and the unemployed, but also those looking actively for work.

In March the participation rate was 62.7%, and it hasn’t grown even while there are more jobs and the unemployment rate is falling. We haven’t seen a participation level this low since 1978. Put simply, many people have left the labor force and stopped looking for work, so there still are plenty of competitors for new jobs, which holds down wages.

Second, job creation is still slow. We are in a “jobless recovery.” Job growth is distressingly low for this stage of the long recovery, now in its 69th month.

It took 6½ years. from January 2008 until May 2014, for the economy to just get back the jobs lost during the Great Recession and we are still lagging behind the normal post World-War II recovery pattern.

Slow job growth is costly for the unemployed and their families. It also slows overall growth, reducing the economy’s potential growth, which further slows the economy, in a spiral of stagnation.

The Congressional Budget Office confirms this self-feeding slowdown. Its potential GDP estimate for 2017 has fallen by 7.3% since its estimate at the start of the recession, which translates into over $320 billion in lost economic activity.

The third reason for low wages is that jobs created in the recovery pay worse than the jobs we lost in the Great Recession. The recovery jobs are concentrated in retail sales, food services, cashiers, stock clerks, and maids and housekeepers — all low-wage sectors.

When the United States is compared with other developed nations on percentage of low-wage jobs, we are sadly the winner. The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development found that the United States has a higher percentage of low-wage jobs than South Korea, Ireland or Poland.

The fourth factor suppressing wage growth is the long-term failure to share productivity gains between workers and business. This recovery is not reversing that trend. According to the Economic Policy Institute, between 1948 and 1979, the gap between overall productivity growth and hourly compensation was 14.7%. But between 1979 and 2013, the gap ballooned to 56.9%, meaning much less of productivity growth found its way into paychecks. So we have economic growth, but workers aren’t sharing in the gains.

This stagnation even hits college graduates. Last December, the U.S. Census Bureau posted a chart with the startling title “Better Educated But Poorer,” showing that many more young adults have a college degree than in 1980, but they are earning less in real dollars.

We won’t see higher wages without two policy changes: more government stimulus to create jobs, and changes in labor market rules to rebalance power between business and workers.

To create jobs the United States should be investing in infrastructure, financed by borrowing at the current virtually zero inflation-adjusted interest rate. Our bridges, roads, ports, railroads, water and power systems, and airports all need repair.

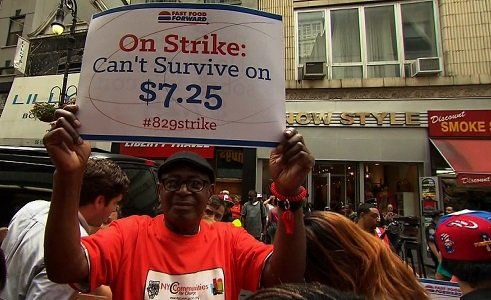

The United States also needs fair rules in the labor market: higher minimum wages, tighter labor market regulations, and encouragement for unions. President Obama has called for increasing the federal minimum wage, but many states and cities aren’t waiting for Washington, and their actions are paying off. Over half of American minimum-wage workers live in states with minimum wages above the federal level.

Walmart recently announced a wage increase to $9 per hour, but this is essentially in compliance with the higher state minimum wage laws. And although McDonald’s will give a $1 per hour increase to workers in company-owned stores, that’s only about 10% of all the chain’s workers, most of whom work in franchises not covered by the raise.

Workers need a voice so they can negotiate a fair bargain with business. Only 7.4% of American private sector workers are represented by a union, and it is no coincidence that the decline in unionization is linked to the stagnation of real wages. The deep decline in traditional unionization is leading some activists to explore new models, but some type of stronger shared voice for workers has to be part of solving the low-wage problem.

These ideas aren’t going to pass in Washington now, given the partisan deadlock between Congress and the President. State and city efforts to improve wages and jobs can only go so far. Without national policy changes, we face a bleak future of inadequate job growth and low wages. America can do better.

Rick McGahey teaches economics and public policy at the Milano School of International Affairs, Management and Urban Policy at The New School. He served as executive director of the Congressional Joint Economic Committee and as assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Labor in the Clinton administration. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.