(NNPA) — Special to the NNPA from the Richmond Free Press

Raymond Harold “Ray” Boone had a snappy response when the infuriated commander at an Army outpost in South Carolina threatened to lock him in the stockade for staying seated when the band played the Southern anthem “Dixie.”

“Let’s go,” Boone, then a corporal, told the furious officer who backed down and let him off with a warning.

With his dander up, Boone sent a letter detailing the situation to then powerhouse New York Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

That resulted in a call from the White House to the commander questioning his actions toward Mr. Boone and his order that soldiers stand at attention for the song.

That story from Boone’s experience in the military speaks volumes about his fearless approach to dealing with wrongs— as a journalist for more than 60 years and as a person.

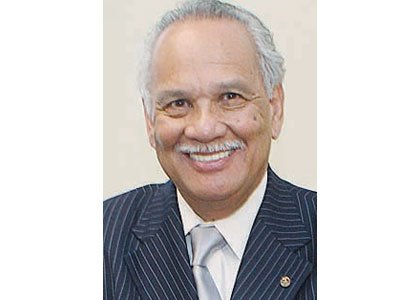

The dapper founding editor/publisher of the Richmond Free Press was a true believer in the First Amendment and the U.S. Constitution. Boone vigorously championed democratic values, with an emphasis on justice and equality for all, never forgetting the harsh segregation conditions he dealt with growing up in his native Suffolk, Virginia.

As one of his admirers put it, “he was the undisputed, undefeated heavyweight champion of journalistic pugilism.”

Boone’s role as an influential community leader ended Tuesday, June 3, 2014, when he lost his battle with pancreatic cancer. He died “peacefully in his sleep with a smile on his face,” said Jean Patterson Boone, his wife of 47 years and Free Press president of advertising. He was 76.

Boone was active in the newspaper almost until the end, said his daughter Regina H. Boone, a photographer with the Detroit Free Press. “He knew what was going on. He was talking about what the headlines should be” for the May 29 edition, she said.

Boone built the newspaper into one of the largest weekly newspapers in the state in striving for lively reporting and strong opinions. He was involved in a variety of crusades. He named his longest running campaign “Vote with your dollars” to encourage readers to use their spending power to reward companies that catered to them and to punish those that didn’t.

He also sought to brighten the city during the winter with his “Love Lights” campaign. Boone also pushed, poked and prodded governors, legislators, mayors and council members to do more business with black-owned and minority firms. As a result of the Free Press crusade, Mayor Dwight C. Jones set a 40 percent goal for minority business inclusion on major city projects, such as the construction of the new jail and four new schools.

Boone made up his own mind about issues and was ready to take his stand no matter what. Last year he announced the Free Press would no longer use the name of the highly popular Washington pro football team, calling it a racist insult to Native Americans.

Boone always credited the education he received in the segregated schools in Suffolk. “It was preached that you could be segregated physically, but you could not be segregated mentally,” he told an interviewer in 2003, “and if you did well in education and you were disciplined, you could overcome the tremendous barriers you faced.”

He followed that mantra, absorbing books and becoming a walking encyclopedia of Black history. Boone said his interest in journalism developed after one of his teachers “told me I could write.”

He took his biggest step into a newspaper career when he approached the local newspaper, the daily Suffolk News-Herald, about writing stories about sports at the Black high schools. His stories began appearing on the sports pages, a first for news about the Black community, all of which had previously been relegated to the “colored” pages.

After earning his degree, he went to Tuskegee, Ala., to work as director of public information. Called into service, he joined the Baltimore Afro-American after he was honorably discharged and became the White House reporter for then one of the largest Black-owned papers in the country.

In 1965, he was sent to Richmond to become the editor of the paper’s Richmond edition and began his rise to prominence. He quickly became a partner with the founders and leaders of the Richmond Crusade for Voters, in an effort to boost the influence of the Black community on the political stage.

Boone would go on to become vice president of the Afro-American chain where he was responsible for multiple editions. Time magazine credited him with bringing “sophistication and verve” to the Black press.

He was proud of sending Afro-American reporter William Worthy to Iran after the overthrow of the shah to provide reports on the revolution. By 1981, Boone moved on to teach journalism at Howard university in Washington before returning to Richmond in 1992 to begin his own newspaper.

While serving as a Pulitzer Prize juror on two separate occasions, he spearheaded a successful effort that resulted in the placement of African Americans and women on the Pulitzer board at Columbia University. He had contacts galore across the country as a life member of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, the National Association of Guardsmen, the National Newspaper Publishers Association and many other organizations.

Along with his wife and daughter, survivors include his son, Raymond H. Boone Jr., Free Press director of account resolution and new business development; his grandson, Raymond H. Boone III; a sister-in-law, Phyllis Riley; seven aunts, one devoted, Dorothy Boone of Suffolk; two uncles; a half-brother, Thurman Boone of Suffolk; four half-sisters, Geneva B. Boone, of Hopewell, Geraldine Boone Clark of Richmond, and Ira Boone and Lolethia Boone, both of Suffolk, and many other cousins, nieces and nephews.