This is part II of a three-part series on longtime journalist Moses J. Newson. Earlier this year Newson was inducted into The National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) 2014 Hall of Fame earlier for his outstanding contributions to the industry.

Moses Newson and other members of the black press constantly subjected themselves to racial slurs, beatings, and other forms of attack as angry whites demonstrated their disapproval of integration. En route, they would brave the dark, winding roads of the South, where members of the KKK lurked and burned crosses.

Despite the danger, Newson and his counterparts did not turn back. They had come there to get something and were not leaving without it – the news story.

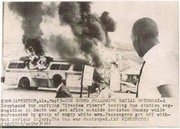

(Courtesy Photo)

Moses Newson outside of a “Freedom Riders” bus which was firebombed by an angry mob near Anniston, Alabama in 1961. Newson was among those aboard the bus during the attack.

Such was the case when Newson was dispatched to Money, Mississippi to cover the Emmett Till murder trial.

Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy from Chicago, was visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, on August 24, 1955, when he reportedly whistled at a white woman named Carolyn Bryant. Four days later, two white men— reportedly Bryant’s husband Roy Bryant, and his half-brother J. W. Milam, kidnapped and murdered Till. The two men were arrested for the murder, thus setting the stage for one of the most famous trials of all time.

“We went there to cover the trial,” said Newson who was writing for The Tri-State Defender of Memphis, Tennessee, the southern outpost of The Chicago Defender. “We had the largest contingent of any black newspaper in the South covering any type of story. We were met by Sheriff H.C. Strider. He indicated the courtroom wasn’t integrated, and the press tables were set up for whites only. However, that eventually changed. They finally set-up tables for us off to the side.”

According to Newson, now 87, the lack of witnesses prompted him and several prominent NAACP members including Medgar Evers to successfully locate overlooked witnesses on various plantations.

“Sheriff Strider didn’t do much to get witnesses,” recalled Newson. “As a matter of fact, he testified for the killers. There were rumors out there that there were some people who had some idea of what had taken place. We went undercover and put on trousers and work clothes that made us look like we had been working on a plantation to locate witnesses, and see if they were willing to testify.”

The effort paid off, as they were able to locate witnesses on various plantations. However, despite such efforts, and overwhelming evidence of the defendants’ guilt, on September 23, 1955, the panel of white male jurors acquitted Bryant and Milam of all charges. Their deliberations lasted only 67 minutes.

“During the trial, the defendants didn’t seem to be too worried,” said Newson. “At the time, people were killed just for getting people to register to vote. But they later spilled the beans and sold the story.”

Protected by double jeopardy laws, the two men sold their story to Look magazine for $4,000 admitting to the crime.

In 1961, Newson also covered the first leg of the “Freedom Riders,” civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated southern United States to challenge the non-enforcement of two Supreme Court decisions which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. Newson was among the passengers on a bus in Anniston, Alabama, when a mob set it on fire with the “Riders” and other passengers still aboard.

“The mob dared us to come off the bus and integrate Alabama,” recalled Newson. “They were banging on the bus with chains and pipes. There was also a long line of cars following us, and one pulling alongside of us to prevent us from gaining any speed. They also punctured the tires.”

He added, “We didn’t know at the time, but there were plain clothes officers on the bus. One pulled his pistol and prevented them from getting on the bus. Someone threw a missile on the bus. I decided to stay on the bus because they were still hitting people getting off the bus. I suffered a few burns. By the time the police arrived, they had burned the bus down to the ground.”

The harrowing moments of that day are still etched in Newson’s mind. “It was one of the ugliest scenes I have ever seen,” he said. “People were on the ground trying to get the smoke of out of their chest. I thought how horrible it was that this was happening to American citizens who were only trying to take advantage of laws to ride aboard integrated buses.”

This series will continue with more about the landmark events that Newson covered during the Civil Rights era, the struggles of today and his induction into The National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) 2014 Hall of Fame.