CNN — Minimum wages are on top of the political agenda in many countries.

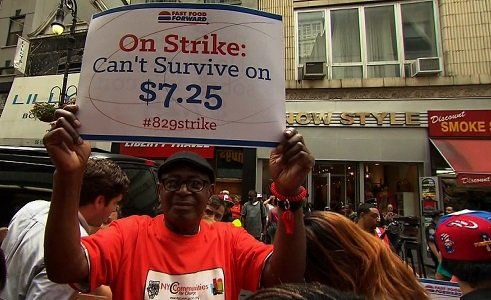

U.S. President Barack Obama’s proposal to raise the federal minimum wage from the current $7.25 to $10 per hour seems blocked by Congress, but individual states and cities are raising minimum wages within their jurisdictions — Seattle’s mayor, for example, proposes a new $15 minimum.

Germany looks set to introduce a national minimum wage for the first time, after months of fierce debates. In the UK, politicians from all the main parties are falling over themselves to find some way to inject new vigor into the UK’s national minimum wage.

Even the free market redoubt of Hong Kong introduced a national minimum wage in 2011.

But it’s not all travel in one direction. Last weekend, 76 percent of voters were opposed to a proposal to raise the Swiss minimum wage to what would have been the world’s highest, about $25 per hour.

So, why this widespread enthusiasm for the minimum wage?

There is both economics and politics at play.

The main argument against the minimum wage is that it destroys jobs, harming those it sets out to help. But evidence suggests that this is often just a scare story.

When the UK introduced its national minimum wage in 1999, critics predicted hundreds of thousands of job losses. The actual impact seemed to be zero.

This experience and other studies have shifted the expert opinion on the minimum wage.

Few dispute that there comes a point at which minimum wage is so high that it destroys jobs. But this does not happen at the current levels of minimum wages in many countries.

The reason the minimum wage seems to have little effect on employment, is that total labor costs do not rise as much as one would expect as costs of turnover and absenteeism are reduced.

Moreover, the incentive to work rises as wages rise for low-skill workers.

Most workers earning are not in sectors where they would be facing international competition so prices rise a little bit.

And many low-paid workers are in an vulnerable economic position and are paid less than the value of what they produce.

So yes, the minimum wage does help low-paid workers — it raises their earnings without harming their job prospects. It helps to reduce poverty.

But it alone cannot solve the problem of poverty.

Many people earning minimum wage, such as students, are not living in poor households.

And many poor households do not contain minimum wage workers.

Indeed, the poorest households are those with no-one in work.

So why the push for higher minimum wage?

Many people think there is something very wrong with an economic system in which someone who works hard is still unable to provide an adequate standard of living for themselves and their families.

Such views have always been common, but are much more common after the crisis when living standards are threatened and the link between growth and people’s welfare seems to have been severed.

In some places, these political pressures seem likely to lead to minimum wages much higher than we have seen in recent experience, perhaps around 60% of median earnings.

This is the point at which many economists get nervous that the negative effects on employment must surely kick in but we do not have many studies to know whether these concerns are valid.

But it seems likely we may be about to find out.

Alan Manning is a professor of economics at LSE and director of CEP’s community research program. His 2003 book, Monopsony in Motion: Imperfect Competition in Labour Markets explains the theory behind minimum wages. Read his blog here. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely his.

The-CNN-Wire