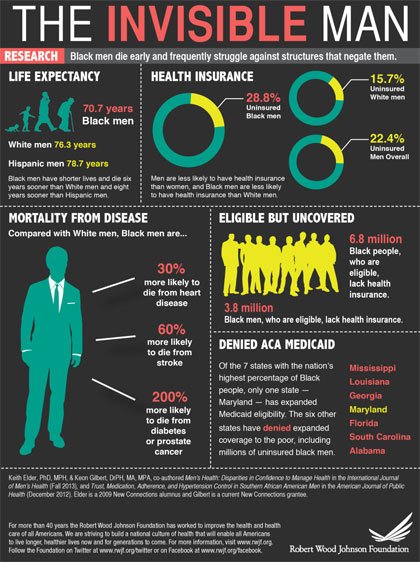

He is missing from the health care system. He is less likely to hold a job that provides health insurance. Otherwise, he is underinsured. Despite chronic poverty that cries out for relief, he often slips through the cracks of a frayed social safety net. Medicaid, focused on pregnant women and children, rarely includes him. He bears a disparate burden of disease. He dies early and struggles frequently against structures that render him invisible.

That reflection, delivered by Keith Elder, flows from the shared mission he and his colleague Keon Gilbert have embraced: bringing Black men into public conversations about health, health care, and health reform.

Elder, PhD, MPH, chairs the Department of Health Management and Policy at Saint Louis University’s School of Public Health. His work moves beyond disparities and dysfunction, expanding the research to expose the breadth and depth of Black men’s health issues from cradle to grave. Gilbert, DrPH, MPH, MPA, an assistant professor in the department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, focuses on outreach, education, and interventions that increase Black men’s access to social capital in order to improve overall health outcomes.

They are co-authors of recent studies: “Men’s Health Disparities in Confidence to Manage Health,” published in 2013 issue of the International Journal of Men’s Health, and “Trust Medication, Adherence and Hypertension Control in Southern African American Men,” which appeared in the American Journal of Public Health in December 2012.

They both credit New Connections—a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) initiative that works to expand the diversity of perspectives informing RWJF program strategy—with helping to enhance their research agendas, and deepening their network of support.

Elder (a 2009 New Connections alumnus), whose research marked some of the seminal data on Black men’s health status, encouraged Gilbert to seek RWJF support. A current fellow, Gilbert is using his New Connections grant to engage Black men around access to the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The goal is to understand how to help those without insurance obtain it, and to persuade those who have it to use it more often by seeking routine and preventive health care services.

Black Men Missing From Health Care Conversation

One of the first hurdles confronting Black men is health coverage. Second, and more fundamentally, many Black men do not readily access health care even when they are insured. Elder notes that Black men with health insurance are two times less likely to use it than other groups.

“Black men are one of the hardest groups to reach. No one is looking to engage them, and they are just not plugged into the systems,” says Gilbert.

“Our published research is important, but the people we need to reach aren’t in the academic world,” says Elder. “They are in the barbershop, on the basketball court, and in communities that are medically underserved.”

Health Disparities’ Effect on Black Men

The health disparities suffered by Black men are stunning: The death rate from heart disease is 30 percent higher than that of white male counterparts; from stroke, it is 60 percent higher. The diabetes death rate is 200 percent higher for Black men, and the death rate from prostate cancer is more than 200 percent higher.

Gilbert points out that another impediment comes from Black men’s sense of self, perceived masculinity, and gender identity. He adds that they are not socialized to go to the doctor on a regular basis: Research shows that men younger than 18 tend to go to the doctor when prompted by a parent, or because they are active in sports, but after the age of 18 health care utilization drops off dramatically.

There is a history in America of rendering Black men invisible, which puts them at greater risk, offers Gilbert. “When men have the opportunity to participate in decision-making, it makes a difference. It increases their engagement and the chances of improved outcomes.” This spills over into policy as well. Gilbert notes that the states choosing to expand Medicaid provisions under ACA now include people with felony convictions, who previously were ineligible for Medicaid coverage. This provides an important opportunity to introduce and expand access to a large segment of excluded and marginalized populations.

Familiar Settings, Fresh Dialogue

Gilbert says men have to be part of the discussion in varied situations. “The conversation has to happen at the dining room table…in churches, barbershops, fraternities, and other settings. There’s a need to really focus and dig deep, to expand the definition of manhood—your need to be healthy, eat a good diet, and get exercise and health screenings.”

Elder underscores the importance of access, coupled with trust in the medical system. “From a medical encounter and management perspective, we need to make sure the experience is good and fruitful. That’s what the Affordable Care Act can do. Men need a good medical home.”

Ending Disparities, Building a Culture of Health

Elder believes the answer is to take steps in the right direction. “Health disparities are not going away in our lifetime,” he says. “Even men who know better don’t do better. Black men still don’t have a 100 percent adherence rate to medical advice.”

The challenges can be combated by a national and sustained commitment to researching Black men’s health throughout the lifespan. No one has really taken a systemic look at Black men. Gilbert adds, “The majority of research is focused on cancer, violence, or HIV.”

Elder advocates for more funding and support at the undergraduate and graduate levels. This will build a pipeline of students who will increase their educational achievement and expand the cadre of scholars devoted to Black men’s health.

“If we don’t have the science, we can’t change the policy and how we deliver care. Who are you going to compare Black men to?” Elder asks.

Keith Elder, PhD, MPH, and Keon Gilbert, DrPH, MPH, MPA, are both professors at Saint Louis University’s School of Public Health.