Less than one month after the original March on Washington in 1963, a notorious hate group proved determined to prevent progress by coldly and viciously reminding the world of the high price of freedom.

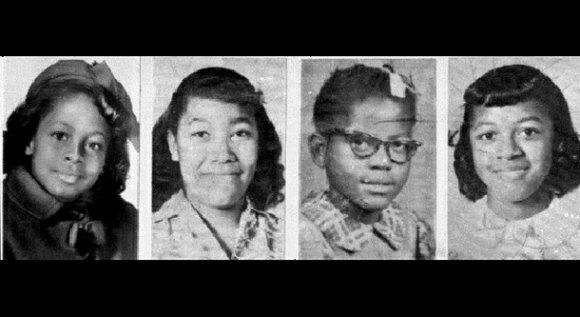

Fifty years ago, on September 15, 1963, about 742 miles south of Washington, D.C., Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, all 14 years old, and Cynthia Wesley, age 11, were killed in a senseless bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

“Obviously, it was such a devastating day and time in so many people’s lives,” said Lisa McNair, the sister of Denise McNair.

The bombing shook the nation in the aftermath of the famous march in which Martin Luther King delivered his electrifying, “I have a dream,” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. on August 28, 1963.

Just three short weeks later, just after midnight on September 15, four members of the Ku Klux Klan planted 11 sticks of dynamite in the basement stairwell of the church, which emancipated slaves founded 90 years earlier. The bomb detonated at 10:22 a.m.

One year after the bombing, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination against racial, ethnic, national and religious minorities and women. The law also ended racial segregation in schools and the workplace.

Earlier this year, the U.S. House and Senate voted to posthumously grant one of the nation’s highest civilian honors to the girls, the Congressional Gold Medal.

Family members of the young bombing victims also received invitations to attend a special ceremony at the National Statuary Hall at the Capitol on Tuesday, September 10, where they were to formally accept the distinguished Congressional Gold Medals.

“It’s just very exciting for me,” said McNair, who was born one year after her sister, Denise McNair, died in the bombing. “Hopefully, people now will learn not to be so hateful and remember how hate and anger harms so many,” said McNair, 48.

The honor, which rewards heroism and bravery, counts as a profound statement in favor of civil and equal rights, said Dianne Braddock, the sister of Carole Robertson.

“I think the medal brings the country together and makes a statement about where we are as a nation,” said Braddock, age 69, who currently lives in Laurel, Maryland.

Rep. Terri Sewell, D-Birmingham, who along with Rep. Spencer Bachus, R-Birmingham, drafted and introduced legislation that led to the awarding of the medals, says that it’s an important moment for the families of the four girls who join civilians such as Pope John Paul II, baseball legend Jackie Robinson, and civil rights icons Martin Luther King Jr., and Rosa Parks in receiving the honor.

In 1977, the murder case, which had lain dormant since the bombings was reopened by Alabama Attorney General Bob Baxley, who won an indictment against Klan leader Robert Chambliss. A jury later convicted Chambliss of murder. He died in prison eight years after his conviction.

Two other former Klan members, Thomas Blanton and Bobby Frank Cherry were finally brought to trial and were respectively convicted in 2001 and 2002, while the fourth suspect, Herman Frank Cash, died in 1994 before he could be tried.

“No matter who you are, or what color you are, when a kid is killed, it throws a different light on things,” said Tom Cherry, the son of one of the convicted bombers, told news reporters in Dallas, Texas, where he now resides.

James Lowe, now a bishop at the Guiding Light Church in Birmingham, attended the church the day of the bombing. Lowe says even some who once pushed back against the civil rights movement had a change of heart after the horrific incident. Now 61, Lowe was only 11-years-old at the time of the bombings. He says that the images remain fresh in his memory.

“I was in a Sunday school room two doors down from where the bomb was placed,” Lowe said. “I remember a loud deafening noise and seeing glass flying out from the windows. Instinctively, I turned my back and shielded my head with my arms and, from that moment on, I lost an awareness of my friends that were in the room. It was as if a dark cloud had enveloped me.”

Birmingham became Ground Zero for hate, the most segregated city in the south, according to Carolyn McKinstry, who recalled seeing the four girls just before the bombing.

“The phone was ringing as I climbed some steps and I went into the office and answered the phone and it was a male voice that said, ‘just three minutes,’ and hung up,” said 64-year-old McKinstry, the author of “While the World Watched.” “The bomb exploded and I heard the windows come crashing in. I was a little bit in shock. At the moment it exploded, I was trying to process what had happened. I was not familiar with death, the loss of kids, but the girls were gone and I knew I was never going to see them again.”