(NNPA) — As a baby-boomer who grew up on war movies, I thought of veterans as various forms of heroes. I knew that in going to war some soldiers died; some were wounded; others came home…and that, I thought, was that. While I vehemently opposed the United States war of aggression against Vietnam for many years, I did not think much about what it actually meant to have fought in that war nor did I consider the less obvious wounds suffered by those who engaged in combat.

Bill Fletcher, Jr.

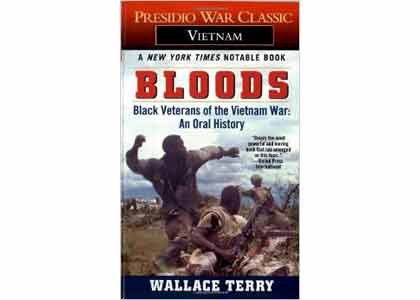

Wallace Terry’s now famous book “Bloods: Black Veterans of the Vietnam War: An Oral History” was eye opening, as was interacting on a closer level with veterans of the Indochina War. Getting close to veterans was not particularly easy for reasons I will address below, meant casting away virtually everything that I had learned in watching war movies. With the possible exception of the post-World War II film “The Best Years of Our Lives,” the U.S. media pays little attention to the plight of the combat veteran.

Even in the case of World War II, where veterans returned home as heroes, their sacrifices and the horrors that they witnessed— and sometimes perpetrated— have been quickly ignored. Combat veterans are expected to pick up from where they left off and get on with their lives, much the way that others of us who have experienced traumas are regularly treated.

Vietnam War veterans were hard to get to know. I do not mean that they were or are rude or unfriendly. Rather, there is a part of most of them that they are reluctant to share. At first I thought that this reflected some sort of attitude towards me, given that I had not been drafted, had not served in combat and had opposed the war. It turns out that it was something entirely different.

In case after case, combat veterans were simply surprised that I gave a damn. Their reluctance to discuss their experiences seemed, more than anything else, to reflect a defensiveness brought on by experiencing, time and again, a combination of lack of interest, denial, and impatience on the part of non-veterans regarding what they— the combat veterans— had seen, heard and done.

While living in Boston in the 1970s and 1980s, I came to better understand the critical need for supportive environments for Vietnam War veterans. There was no real reason for them to trust people like me, and the first thing that I had to appreciate was that it was nothing personal at all. They had no reason to trust that any of us who had not been in combat not only could “get” what they experienced but that we cared to shut up and listen to the stories that they told. In many respects that is why reading Bloods was so important for me: I had to sit there, shut up, and listen to voices tell stories that I would not otherwise have heard.

Bill Fletcher, Jr. is the host of The Global African on Telesur-English. He is a racial justice, labor and global justice activist and writer. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook and at www.billfletcherjr.com.